- 265 Campus Drive, G3065

- talee13@stanford.edu

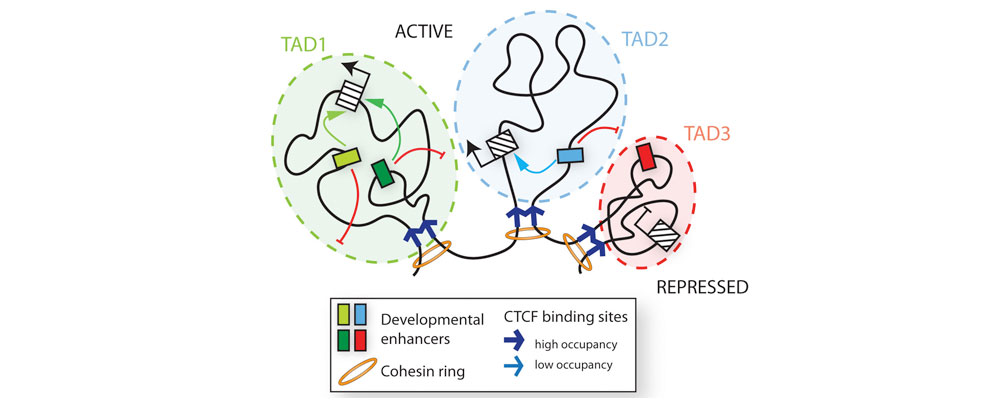

Interactions between the genome and its cellular and signaling environments, which ultimately occur at the level of chromatin, are the key to comprehending how cell-type-specific gene expression patterns arise and are maintained during development, or are mis-regulated in disease. Central to cell type-specific transcriptional regulation are distal cis-regulatory elements called enhancers, canonically defined as short noncoding DNA sequences that act to drive transcription independent of their relative distance, location or orientation to their cognate promoter. A major area of investigation in our laboratory is focused on general mechanisms of long-range gene regulation by enhancers, which can activate their target genes over tens or even hundreds of kilobases of genomic distances. We are striving to understand how enhancers are activated in response to developmental stimuli, how they communicate with target promoters, what is the dynamics of this process in living cells, and what is the role of chromatin context in priming or restricting enhancer activity. You can learn more by reading these representative papers:

While studies in model organisms have led to great progress in unveiling the conserved fundamentals of gene regulation, many aspects of development that are unique to humans and other primates remain unexplored. Our laboratory uses Cranial Neural Crest Cells (CNCCs) as a paradigm to study how genetic information harbored by regulatory elements is decoded into a diversity of functions, behaviors and morphologies. CNCCs are a transient embryonic cell group which delaminates from the neural tube, migrates long distances and acquires an extraordinarily broad differentiation potential, ultimately giving rise to most of the craniofacial structures and determining their individual and species-specific variation. Over a third of human congenital malformations are linked to CNCC dysfunction, including over 700 syndromes with craniofacial manifestations – a staggering number. Interestingly, craniofacial syndromes are often caused by heterozygous mutations in general regulators of transcription or ribosome biogenesis, which are broadly expressed across tissues and required for maintenance of fundamental cellular functions. Why and how mutations in these general factors selectively impact some, but not all, developmental programs remains largely unknown. The goal of our ongoing research effort is to understand how variation in gene expression translates into differences in CNCC behavior, leading to the emergence of normal-range and disease-associated morphological diversity in the craniofacial form. This gene expression variation can result both from the trans-regulatory differences, such as those associated with mutations of transcriptional and chromatin regulators in craniofacial syndromes, and from the variation in cis-regulatory sequences like enhancers. To understand both mechanisms of variation and their cell type specificity, we are using human pluripotent stem cell differentiation models that recapitulate induction, migration and differentiation of CNCCs in the dish and facilitate modeling of human neurocristopathies. To study impact of regulatory changes on facial morphology, we are combining these in vitro models with the in vivo work in mice and frogs and, in collaboration with human geneticists and anthropologists, with the morphometric measurements of craniofacial features in human populations. You can learn more by reading these representative papers:

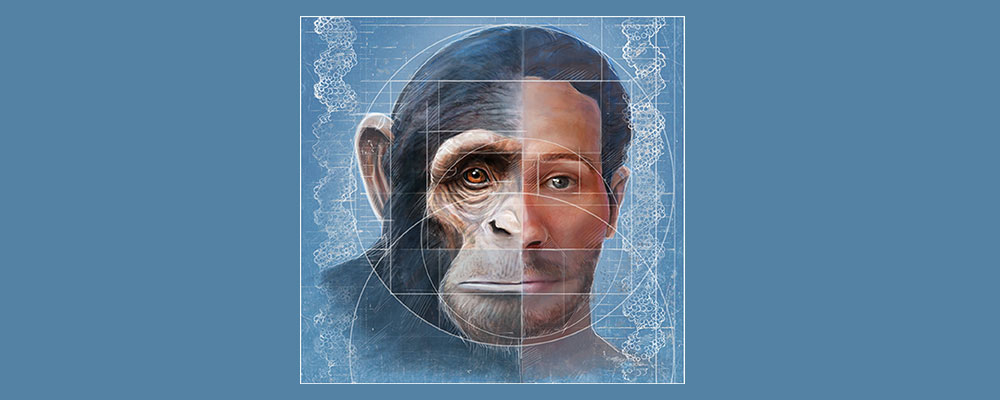

Since the seminal discovery that the protein-coding regions of the genome remain largely conserved between humans and chimpanzees, it has long been postulated that morphological divergence between related species is driven primarily through quantitative and spatiotemporal changes in gene expression mediated by alterations in cis-regulatory elements, but the regulatory principles underlying emergence of human traits remain poorly understood. We recently proposed ‘cellular anthropology’, a strategy of using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from humans and great apes to in vitro-derive evolutionarily important cell types for the systematic discovery of cell type-specific regulatory changes. With this approach, we mapped Cranial Neural Crest Cell (CNCC)-specific enhancer elements that have altered activity since the divergence of humans from our closest living evolutionary relative, the chimpanzee. Importantly, the CNCC derivatives played a privileged role in human evolution, facilitating emergence of distinctively human facial appearance, as well as adaptations and exaptations associated with accommodating a larger brain size, upright posture and speech articulation. Building on this initial work, we are now investigating molecular mechanisms by which the uncovered regulatory changes and pathways influence transcription. Furthermore, the recent availability of high-quality genome assemblies from our extinct hominin relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans, coupled with genome editing technologies, presents opportunities to understand how genetic variations led to human-specific regulatory innovations at a finer resolution. We are complementing these studies with mouse genetics to model impact of cis-regulatory evolution on craniofacial morphology and function. You can learn more by reading these representative papers:

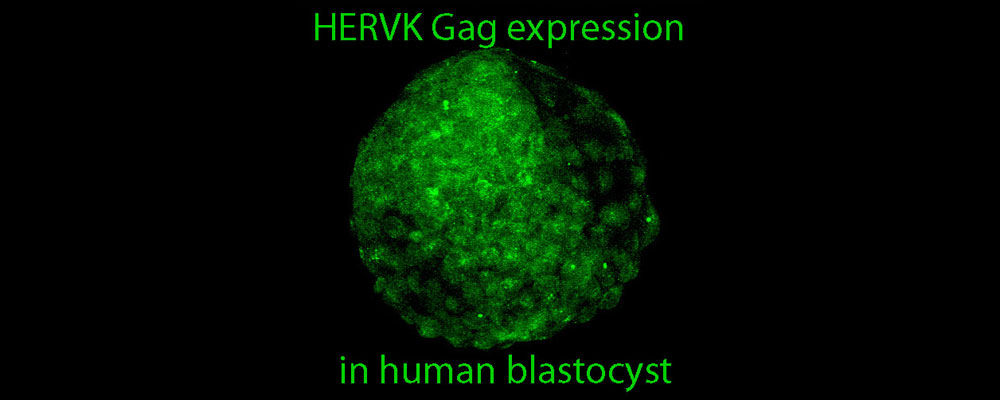

Transposable element (TE) derived sequences comprise nearly half of the human genome. It is not always appreciated, however, that most TEs that are present in modern humans invaded the ancestral genome at various points of primate evolution, but are typically not shared with more distal mammals such as rodents. Thus, TE derived sequences form a vast reservoir of largely primate-specific sequences from which novel regulatory functions can evolve. We are interested in understanding how TEs may serve as a substrate for evolution of species- and tissue-specific cis-regulatory elements for the host genes, and we are investigating a developmental aspect of transposon regulation. For example, we discovered that during human pre-implantation development many TEs escape silencing and are transcribed at discreet stages, with most dynamic and stage-specific regulation occurring at the class of LTR retrotransposons called endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), which are remnants of ancient retroviral infections. One such ERV class, called HERVK, retained coding potential and gives rise to the viral-like particles and proteins that are readily detected in human blastocysts. In contrast, another class, ERV1, is enriched among CNCC enhancers that changed their regulatory activity since the split of humans from chimpanzees. A flip side to TEs serving as a playground for regulatory innovation is that mobile transposons are parasitic elements that pose an ongoing threat to the genome, and thus must be controlled by the host cell. The non-LTR retrotransposon Long INterspersed Element-1 (LINE-1 or L1) is the only currently mobile autonomous TE in humans, with roughly 500,000 L1 copies comprising about 17% of the human genome, of which over a hundred are thought to remain retrotransposition competent. New L1 insertions contribute to inter- and intra-individual genetic variation, in some cases resulting in disease. We are striving to understand how L1 retrotransposition is controlled by the host, especially at the chromatin level, and how and when during development, active L1s can escape this control. You can learn more by reading these representative papers: